While Anthony became involved in various unofficial extracurricular activities, Alec and Dan formed several anonymous blues and country-folk acaoustic acts that culminated in the legendary-in-their-own-minds, Violent Femmes-ish Chicken Truck.

All three were dying to get out of there, and to the relief of many, none stayed in Massachusetts for long: Dan transferred to Macalester College in St. Paul, Alec went to college at TCD in Ireland for 3 years, while Anthony became involved in numerous adventures, including a commune in California. Somehow, they stayed in touch.

Alec had gone electric and Anthony had learned the drums. They moved into a rented house and practiced in the basement. Soon they were joined by Dan and they formed a band with bassist Mishe Eddins called Ophelia's Backporch Revolution, which was a smattering of Camper Van Beethoven, Southern Culture on the Skids, Joy Division, the Velvet Underground and Uncle Tupelo. They played three shows over six months. When Mishe quit and Dan finally lost patience with their excessive volume and amateurish whims, Alec and Anthony formed a series of short-lived bands with crack guitarist (and former Cracker roadie) Steve Seta: gloomy Nico-ish folk-pop The Flanderses with singer-cellist Bernadette Campbell (later of Feliz Gomez), and the Stooges-obsessed Youth Hostel.

When Anthony tried to call it quits, Alec enticed him with a gimmick inspired by the Wedding Present: to record one new song on 4-track each month for a whole year. They re-worked Alec's old Ophelia's Backporch Revolution song "(You Loved Me For) My Cigarettes"--stripping it of its folkiness and adding a much nastier guitar sound, and the seed was planted.

Meanwhile Adam Walker, who had played in Chicago band Creosote,

was working on a youth rehabilitation camp out in the country.

He came by to borrow some flour while Alec and Anthony were four-tracking

the country hate song and lent background vocals to it. He had

some songs of his own, it turned out, and a name for a band. They

picked up bassist/violinist Shana, a student at UNC, while trying

to get change for a bus in Carrboro. Shana's screeching, amplified fiddle worked perfectly with the

drunken country-punk ethic of the other three, and Shinola was

born.

This went on for a while...

They finally played their first show in January of '95 at the Cat's Cradle, opening for Pine State (who were still young) and Trailer Bride at the invitation of Chris Riser, who had heard "Cigarettes" on WXYC, the local college radio station. A whole slew of Monday and Tuesday night gigs followed.

In late spring of '95, they recorded four songs with Chris Palmatier

of the proto-mathrock band Joby's Opinion at Adam's house in the country. Two of those songs appear on

the "Vodka" single.

Shortly after the single was finished, Shana was called by Jesus to leave her godless cavorting around with marxist musicians behind. She now lives in San Francisco with our old pal "Shaky" John Haywood.

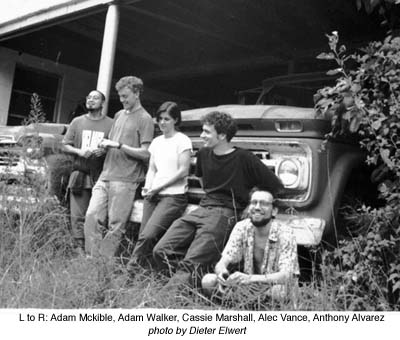

But all was not lost. Alec recruited Mayor McCripple of Pine State to play bass guitar and the Farfisa organ. Adam Walker's longtime love interest and professional violinist Cassie Marshall moved up from Texas (where she had just played in the orchestra on the Page/Plant tour) to make his life complete and play in Shinola mk. II.

Saturday's weekly practice at Alec's house in Carrboro became an excuse to go to a new BBQ shack, taking full advantage of North Carolina's greatest culinary resource. Mayor McCripple became the godfather of such ventures (though ironically his NYC birthplace was further from Q country than anyone else in the band). Alec and the Mayor, drunk on bourbon at the Local 506, decided to make the band's mission two-fold: Not only to play crappy music, get sloshed, and leer at girls; not just to force trite commie propaganda down their victim's throats; but to spread the BBQ gospel while doing so. To document, meticulously, every bite in every county. The Shinola BBQ site inspired and educated all.

Meanwhile the band played all sorts of gigs. The vinyl craze being

over, no one would touch the single. Indie rock bands all over

Chapel Hill lost the will to live, and yet Shinola foolishly struggled

on. Rejection notes from labels were greeted with excitement:

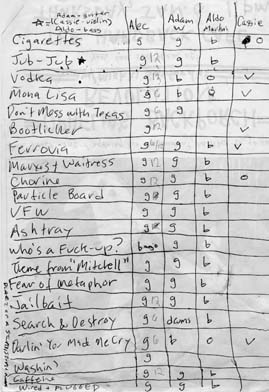

It was rare to drum up even a response. Yet somehow the setlist

grew to over 30 songs, radio sessions and gigs were as frequent

as ever, and the band continued to tape practices and work on

old songs. It was time to take it to the next level.